The Passages Of Life – YFPC Inmates Share Writing Through National Program

April 3rd, 2013

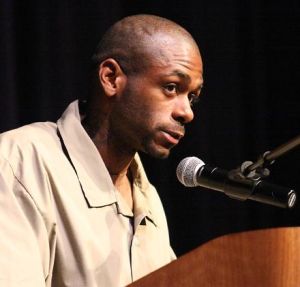

Mark Payne reads his story as one of four Yankton Federal Prison Camp (YFPC) inmates participating in this week’s creative writing presentation at Mount Marty College. MMC English professor Jim Reese is one of five artists-in-residence throughout the country who are part of the program for federal prisons. He is serving his sixth year with the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) project. (Kelly Hertz/P&D)

BY RANDY DOCKENDORF

randy.dockendorf@yankton.net

Mount Marty College professor Jim Reese listened with pride this week as his creative writing students read their work on the MMC campus.

Then, when the program ended, he helped escort the four men back to the Yankton Federal Prison Camp.

Since 2008, Reese has been one of five artists in residence throughout the country selected for a National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) program. The initiative works with the U.S. Department of Justice’s Federal Bureau of Prisons, which includes the Yankton facility.

Through the writing process, inmates discover more about themselves, Reese said. In the process, they rebuild their lives and avoid a return to prison.

“You can teach a guy a trade while in prison, which is fine and good,” he said. “But unless you teach somebody to come to terms with the emotional instability that brought them to prison in the first place, you’re sending an angry person right back to prison.”

Most YFPC inmates aren’t violent offenders, but they may feel rage or broken relationships in their lives, Reese said. “The guys in my classes have made mistakes and some misdirected decisions,” he said.

As a writer in residence, Reese established YFPC’s first creative writing workshop and publishing course. He also edited an annual journal, “4 P.M. Count,” which features creative writing and visual artwork by inmates. “4 P.M. Count” isn’t for sale but is provided free to individuals for educational purposes.

The rage, hurt and unresolved issues were evident during Tuesday night’s program on the MMC campus. The four inmates read their work from “4 p.m. Count,” named after the daily inmate check at federal facilities.

• Mark Payne explained he was a product of his environment. He spoke of growing up in San Diego, getting shot three times at age 14 during a robbery gone wrong. He fathered a child, as he put it, “when still a child myself.”

But perhaps the greatest shock came upon learning, while in prison, that his 17-year-old sister, Monique Palmer, was killed during a gang dispute. Payne dedicated his writing in her memory.

“When my sister was murdered, I changed. I was to be her protector, and I have realized the path of my life must be different if I was to survive,” he said. “Not just survive, but live, and contribute to the world as a man, a father, a husband, a son: life’s essentials.”

• Scott Swanson wrote about “The Red Box” that he rediscovered while helping his mother clean out a junk collection. The red box contained a journal, given to him as a boy, that allowed him to express his inner thoughts.

Now, as a man, the journal has brought back a rush of memories. However, he didn’t have the key and chose to keep that part of his life closed rather than break open the journal by other means.

“It wouldn’t be right. Not without the key,” he said.

• Thomas Schroeder wrote about “The Black-And-White Photo In The Pretty Silver Frame.”

In his story, Schroeder talked about his college relationship with a young woman, named Carla, who sought to learn more about her father killed in the Vietnam War. With Schroeder’s assistance, she learned her father had earned a Silver Star for valor after his platoon was ambushed by the Viet Cong.

Schroeder asked Carla how she felt about learning her father’s story.

“For some reason,” she said, “I feel different, better. I think I understand my Dad a little more. I know how and why he died. I don’t feel as abandoned. It’s like we have a connection, I sense him with me, and somehow, I know he loves me.”

• Sean Sunday wrote on his life’s path in “Rendering Decisions.” He was raised amidst the struggles of a single-parent household, and he himself would later father a child as a young man. He chose drug dealing over an athletic scholarship, which led to prison and tore apart his relationship with his family and others. The mother of his daughter died, and he learned in prison that he had fathered other children.

Sunday has worked to rebuild his relationship with his adult daughter.

“I pray that when all this is said and done, we will put aside any differences and live a life that is built on love and bonds of affection,” he said.

Getting Started

When it came to creating the inmate writing program, MMC and YFPC already enjoyed a 23-year relationship.

Sister Cynthia Binder from MMC and Maureen Steffen, the YFPC supervisor of education, worked together on college classes at the federal prison. Sister Cynthia and Reese recently received a Distinguished Public Service Recognition Award from the prison for their work with inmates.

At the time, Steffen was familiar with Reese’s work with the MMC student publication “Paddlefish” and approached him about participating in the writer-in-residence program.

Reese was accepted for the program, and he read as much as he could on arts in correctional facilities. He also made trips to San Quentin to see how arts programs work in maximum security prisons.

“I’d be lying to you if I told you I wasn’t intimidated at first, but that’s par for the course,” he said.

When beginning the Yankton program, Reese’s initial goal was to help prisoners become better writers. But in the process, the inmates became better persons — and so did he.

Reese admits, as much as he had prepared, he wasn’t ready for an inmate question.

“One of the students asked me the first day: ‘What’s the difference between poetry and prose?’” Reese said. “I realized then no matter how much I planned, this was going to be a new teaching environment for me.”

However, Reese has grown to love teaching the inmates, who are attentive and want to become better writers. He tells the inmates to focus on their message and not the technical details.

“I tell them, ‘Forget all those grammar rules. What is brewing inside you? We’ll learn some of the rules soon enough. But let that voice out — let it ride. Forget about all the rest,’” he said.

The weekly 3 1/2-hour writing sessions unleash a burst of passion and emotional frenzy among inmates, Reese said.

“One of the assignments was to write a letter to a younger man. The young man can be anyone — your younger self, a son or perhaps a victim. It immediately triggered a voice that had been holed up for years,” he said.

“The guys started exploding on the page — they started writing, really writing, and realized, ‘This is it; I may be stripped of everything here for now, but no one, by God, can take my voice away from me.’”

That voice has given inmates great personal power, Reese said. “This is their reward. They want to be heard and to tell their story,” he said.

Another Voice

Last year, Reese used an intern for the first time with the inmate writing program. Cody Ball, then an MMC senior, took up Reese’s internship offer.

The previous year, Ball and other MMC creative writing students had taken a drawing class at the prison to learn visual arts for their work. Ball became fascinated with his inmate instructors.

Ball admitted he was intimidated with his first visit to the prison for drawing class.

“A guy that was 6-foot-8 introduced himself to me. He had a picture of his daughter and wife that he was using for a drawing,” Ball said. “I didn’t know him at all, but he opened my eyes to what people were like. My perception (of inmates) became really different.”

As a result of the art class, Ball jumped at Reese’s offer to assist the following year with the inmate writing class. Ball had previously seen the inmates’ drawing creativity, but he wasn’t prepared for the depth of their writing ability.

“I was blown away at the talent and the quality of work. I didn’t expect this high a level,” Ball said. “I was jealous of the inmates (as a writer). They have interesting lives and experiences, and they want to get out and make people understand.”

Inmates who take the class tend to be better thinkers and want to change their lives, Ball said. He was skeptical at first, thinking the inmates would produce only what they thought the instructors wanted.

“But they really tapped into themselves, which was our goal,” he said.

Ball graduated from MMC last spring, and he currently works as an admissions counselor and basketball coach at Northwest College in Powell, Wyo. Ball said the internship continues to influence his life, including his work with prospective students who may come from disadvantaged backgrounds.

“How many other people can say they had the opportunity to teach creating writing in a federal prison?” he asked. “But it also really opened me up as a person. I don’t judge people based on where they come from or where they’re at with their lives.”

As a sign of the program’s importance to him, Ball drove nearly 12 hours to Yankton to participate in this week’s program at Marian Auditorium, which included readings from MMC students as well as inmates.

“These inmates gave me so much in my life. They respected me, and they learned from me,” Ball said. “They were also reading in an unfamiliar place (at MMC), and I thought it would be helpful if they had a familiar face with them. I shook hands with them afterwards, and Mount Marty students stayed to shake hands with them, too.”

Building For The Future

As part of the Great Plains Writers Tour, Reese brings in renowned authors who also speak with the inmates in the writing program. The visitors have included George Belgiere and David Lee.

“I bring in guest writers from throughout the country. The 2008 American Book Award Winner, Maria Mazziotti Gillan, had them in tears,” Reese said. “The students write letters to the authors after they visit, and then the authors respond with letters back to the whole class.”

Spearfish writer Kent Meyers responded with a 14-page letter to the students because he recognizes the importance of the inmates’ need for a voice, Reese said.

“I guarantee there are a couple of the inmates who will write a book after they get out of prison,” Reese said.

The MMC professor would like to create a national journal using various prisons.

The nation has a huge stake in making the writing program work, Reese said.

“The number of prisoners in the federal system is 2.5 million and growing,” he said. “We don’t want them to go back to the old ways that led them to prison. We want them to receive an education.”

According to a 2009 federal corrections report, inmates who complete an associate degree are 70 percent less likely to return to prison. Those with a GED are 25 percent less likely, and those with a vocational certificate are nearly 15 percent less likely.

A U.S. Department of Justice report says that “Prison-based education is the single most effective tool for lowering recidivism. According to the national Institute of Justice Report to the U S Congress, prison education is far more effective at reducing recidivism than boot camps, shock incarceration or vocational training.”

“I believe the National Endowment for the Arts’ writer in residence opportunity fulfills both areas,” Reese said. “I do hope that such programs continue throughout the country.”